On the morning we were scheduled to arrive in Zagreb, Croatia our train stopped at the small town of Dobova, Slovenia near the border. Two guards boarded the train and systematically checked each passenger’s identification. When they reached us, the Slovenian guard leafed back and forth over the stamped pages in each of our passports and eventually asked me how long we have been in the Schengen. I told him that we’d been in France and Belgium for the last month and a half and added that I’ve been keeping track of our time in Europe and I’m certain we have not overstayed our visa. He looked back through our passports and started counting on his fingers and even had a short conversation in Slovene with someone over the radio. I asked him if everything is okay and he pulled out his exit stamp, stamped both of our passports and handed them over to the Croatian guard. He assured usthere was no problem, but warned that isn’t just our most recent trip that counts against us. The other guard stamped our passports with his entry stamp, returned them to us and added that Croatia is also in the European Union. I told him I understand, but verified that our Croatian visa is different than the Schengen visa. Satisfied, the border guards moved on to the next passengers and eventually we continued our journey to Zagreb.

What’s a Schengen?

You may be wondering what just happened. Why were we given extra scrutiny and a stern talking to by these fine young men patrolling their borders? Why were we stopped in the first place, aren’t all borders between European countries open? Why did the Croatian guard mention that Croatia is a part of the EU even though Croatia has its own visa? Wait, how are you still in Europe when a tourist visa only allows you to stay for 90 days? There are no quick and easy answers to these questions, at least not any I’d feel comfortable giving. So pull up a chair and let’s dive right in.

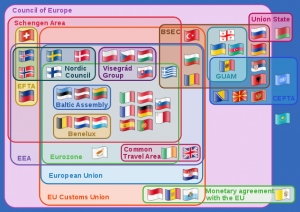

I found the above eye chart on Wikipedia where it attempted to explain which countries are members in the various unions, councils, agreements and areas in Europe. As you can see, Europe is not quite as united as it may seem from the outside. It might be easier for me to define what the Schengen Area is not before I say what it is. It is not the continent of Europe, or even “continental” (non-UK/Ireland) Europe. It is not the European Union. Norway and Switzerland are in the Schengen but not the EU and there are even more countries who have joined the EU, but are not yet a part of the Schengen. It is not the Eurozone (countries using the Euro currency). There is a surprisingly long list of EU countries that have their own currency.

Okay, enough of what it isn’t, what is the Schengen Area? It is a group of 26 countries (and growing) who have signed the Schengen Agreement to abolish passport and border controls at their mutual borders. It is named after Schengen, Luxembourg where the first agreement between Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, France and Germany was signed in 1985. Over the years it has gradually expanded to cover most of Europe with the countries of Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Romania being the next four countries required to join as a part of joining the EU (although it has not happened yet mostly for political reasons). The UK and Ireland have opted out of the agreement and instead have their own open border policy between the two countries. In recent years, there have been cases where certain internal border controls have been reinstated due to terrorist and refugee migration threats.

What does this mean for tourists?

Disclaimer: I’m writing this primarily from the perspective of a US passport holder. In some cases the rules may be the same for other non-Schengen passport holders, but I have no personal knowledge of how it works in practice. This is also being written in April of 2018, by someone who is not an immigration lawyer, so please check the official Schengen web site for the latest rules.

For a casual tourist, the Schengen Agreement is wonderful. You arrive in a Schengen Area country, get your passport stamped and now you can travel unrestricted anywhere within the Area for a period of up to 90 days. Technically you need to carry your passport (or at least a copy of it and your entry visa stamp) everywhere with you since you could be asked at any time to show it to the authorities. Honestly, we’ve never been randomly asked for our passports in any of our travels other than when renting a car or occasionally when checking into a hotel, but we usually keep them with us anyway. The 90-day restriction rarely comes into play as it is much longer than the typical US vacation.

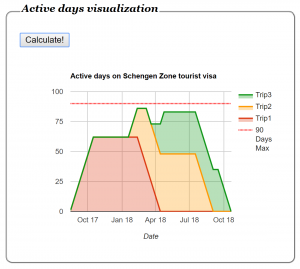

On the other hand, the Schengen Agreement can be a bit of a headache for the long-term nomadic traveler. The full visa policy is 90 days in any 180 day period. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve entered and exited. To remain in compliance, you have to look back 180 days and count up the number of calendar days you were in the Schengen. If it is 90 or less, you’re fine, more than 90 and there could be problems. The 90/180 rule means one can’t use a “visa run” of a day or two to a non-Schengen country in order to get a fresh 90-day Schengen visa. Realizing that these rules can get confusing the more times you enter and exit, the European Commission has an official Schengen visa calculator to help travelers stay in compliance. Being the geek I am, I created my own calculator to make sure I understood how the visa calculation really works. It also allows US travelers to enter dates in our more familiar MM/DD/YY format and then it creates a chart making it easier to visualize how the accumulation and eventual reset of visa days works. Feel free to give it a whirl.

Obviously, the next question many ask is what happens if you overstay a Schengen visa? The best answer I can come up with is, “It depends”. Enforcement and fines of the Schengen visa rules are left to the individual countries. Searching the traveler forums, I found varied accounts that range from “They didn’t even look at the stamps in my passport” to fines of hundreds or thousands of Euros, deportation, being banned from re-entering the Schengen for a year or two, or even jail time. Our personal experience over the last year of travel is that Schengen border guards are much more diligent now than we’ve ever noticed them being before. Overstaying your visa for a few days may result in only a slap on the wrist, but why run the risk?

How do you travel in Europe for longer than 90 days?

When we were researching our trip, I scoured the internet for ways to stay in the Schengen Area for longer than the 90/180 limit as a tourist. Not surprisingly, it is a pretty common question posted to the various traveler forums. Without fail, the answer ends up being “No” it is not possible to extend a short-stay Schengen visa. I did find anecdotal evidence that it is possible to get an “emergency” extension. At best it would be due to some real emergency like a hospitalization and who wants to extend their European tour because of that.

The good news is there are alternatives. We’ve been traveling in Europe for the last 8 months by not spending all of our time in the Schengen Area. Last fall and winter we spent three months in the UK and Ireland. They allow United States citizens a tourist visa for 6 and 3 months respectively. Travel between the two is virtually unrestricted, meaning no border checks to get your passport stamped at. Therefore I have no idea how one would attempt to maximize their time there, legally staying for a combined 9 months. This spring and summer, we will be in Eastern Europe and the Balkan Peninsula taking advantage of the non-Schengen countries in that part of Europe (Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, Macedonia, Kosovo, Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus, Romania, Bulgaria and Cyprus). Each country has a separate tourist visa, often for 90 days. Using my visa calculator, I’ve mapped out our Schengen visa usage since we started our trip last August.

The Schengen Agreement provides a common set of rules governing the short-stay 90-day visa, but leaves long-stay visas (from 3 months up to 1 year) to the discretion of the individual countries. I’ve only read about these options and have no first-hand knowledge of how difficult they are to obtain. We haven’t felt the need to pursue any of them further yet. Long-stay visas seem to fall into one of three categories. First is the student visa. Enroll in certain accredited programs of study, and you can apply for a visa for up to one year. There is an entire industry offering trip packages entitled something like “Learn Spanish in Barcelona!” These companies will help their customers enroll in classes, find housing and apply for the proper visa. Some countries make it possible to obtain a long-stay tourist visa, the most common I read about being France and Sweden. There are going to be requirements such as proving that you have adequate funds and health insurance as to not be a burden on the public systems there. You also will not be allowed to work and may have to already signed a lease or prove you are staying with friends or family. The final category is to apply for a work visa. In many cases this requires an employer to sponsor you in advance. There is no applying for the visa and hoping to find work when you get there. If you’re young enough, many countries have a working holiday visa which waives the pre-requirement of employment, but is restricted to citizens of certain countries and to people under a certain age (the cutoff is normally 30). For digital nomads, Germany has a visa geared toward freelancers and Estonia recently announced a program which sounds similar. The German visa does require proof of health insurance and accommodations, a business plan and some amount of startup capital or proof of income in case you don’t find any gigs while you’re there. All of these options require a time and/or financial commitment that may not appeal to the “average” nomadic traveler.

Doing the Schengen Shuffle

I had high hopes to coin a new phrase when I came up with the title of this week’s post. Alas, I just googled it and found that, while not common, there are others who have used it before me. The bottom line is that the Schengen visa rules, while restrictive, can be worked around with a little planning and diligence. We’ve been bumming around Europe for the last 8 months and don’t plan on moving on to another part of the world until sometime in early 2019. Until then, we’ll keep on shufflin’.